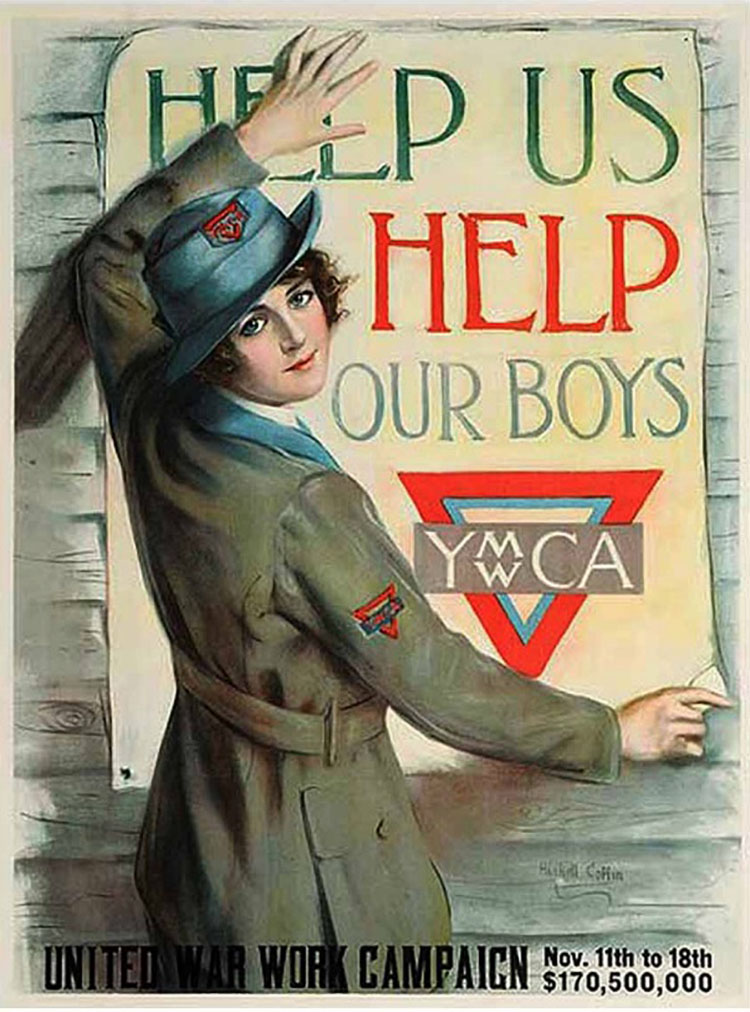

Mankato native, Marguerite Marsh, answered the call when the United States branch of the YMCA took a bold step and opened its service to females for the first time in July 1917.

Soon after the United States joined World War I on April 6, 1917, the national YMCA offered its support at home and abroad. The non-profit, community-based organization assumed military responsibilities on a scale that had never been attempted in the history of our nation.

When war was declared, the YMCA immediately volunteered its support at home and abroad. The YMCA gave soldiers a place where they could get away from the harsh realities of the war. They organized canteens at the front lines in France. These huts or tents were run by “Secretaries,” who provided coffee, writing materials, books, a gramophone and records or a moving picture show several times a week for the soldiers.

Some Americans thought that women would not hold up to the physical and mental strain of war work, but many women stepped up to the challenge, going to France.

Family

Marsh was born in Mankato on Independence Day in 1890. Her mother died when she was only eleven years old and her father left her in the care of her elderly grandparents, John Q. and Sarah (Hanna) Marsh, early Mankato settlers.

Sarah Marsh died two years later leaving Marguerite alone to care for her aging grandfather. Marsh graduated from Mankato High School in 1909 and was an active member of the First Presbyterian Church working with youth. After the death of her grandfather in 1915, she enrolled at the University of Wisconsin in Madison to study home economics.

Last Sunday afternoon I watched an air battle at some distance. We never know whether it is a practice fight or a real oneMarguerite Marsh

Marsh enlisted with the 82nd Division in November 1917 and was one of many women who served along with 13,000 YMCA workers in France. She was assigned to a YMCA café at Tours, France, and was later given the rank of secretary in charge of a canteen at Gondrecourt, with the First Army school.

Back in Mankato, the First Presbyterian Church published a newsletter called Our Church Life. In addition to church news, it contained letters written by local servicemen and women. Below are excerpts from letters written by Marguerite.

December 11, 1917

In a telegram sent to the Rev. Paden, Marguerite tells him that she hopes to depart for France on Dec. 19. Soon after arriving she worked canteen service in the largest café at Tours, outside of Paris, serving three meals a day in addition to other duties. “Before leaving Paris, some of the group visited the American Hospital there. We could hardly get away. Though there was no one there from our part of the United States, we were welcomed like long lost friends. The boys were all eager to see anyone from America.”

April 16, 1918

Writing from “Somewhere in France” with the weather cold and damp, she was rooming with a friend at the YWCA Hostess House and was eager for “real canteen work” at one of the barracks.

May 17, 1918

She wrote that she was “muchly excited” over the granting of their repeated request to be transferred nearer the front and their preparations for the approaching transfer—to what point she did not know. Our Church Life reported that her aunt, Mrs. John R. Beatty, received a letter from Marguerite’s superior officer regarding her work: “She is doing really good work here and is a credit to her country and to her family.”

She is doing really good work here and is a credit to her country and to her family.Marguerite Marsh’s Superior in the YMCA

July 1918

She wrote of the few weeks spent starting a canteen twenty-eight miles from the front: “Starting a canteen means bushels of work…We furnish the boys stationery, envelopes, pens and ink—free. The writing tables are in use most of the day. A bunch of boys who came in recently from the South and can not read and write so we are arranging classes for them. Last Sunday afternoon I watched an air battle at some distance. We never know whether it is a practice fight or a real one.” Several weeks later she writes about the abandonment of the canteen and her transfer to a large canteen at the divisional headquarters.

August 23, 1918

“Back again and working harder than ever in a hut which serves thousands of men. I never saw so many hot, dusty boys in my life. They come in on trucks so white with dust that they bear no resemblance to human beings…There is a beautiful full moon and we are congratulating ourselves on our escape from the air raids. We have had bombs to the right of us and bombs to the left of us but so far have remained untouched. I am writing to the accompaniment of a beautiful band which is playing on the shady side of the village street. There is something incongruous about that band. It has played each afternoon for a week. It gives me a queer feeling. Even as I write the sound is drowned by the rumble of army trucks. Music gives war a stagy effect which it is far from having. It is quite too real.”

Oct. 21, 1918

“I am ashamed to tell you how comfortable I am. I have a room all to myself, with two other American women in the same house—‘Y’ workers also. The canteen work is very hard but with such comfortable living conditions, I don’t mind. I work every night until ten or half past. The cook from one of the Company messes made doughnuts for us yesterday afternoon and last night we were just swamped. We had Billy Sunday’s trombonist at our hut Sunday evening. He gave such a straightforward talk which did us all good. We lead such double lives over here. Underneath, our hearts ache for the boys suffering in the hospitals or standing in the cold mud of the trenches; at the same time we must joke, play around with, and try to help keep up the spirits of the boys in the back areas who are waiting their turn…The other day, on one of the few sunshiny afternoons which we have had, Miss Tyler and I went up on the hill back of the village. In the distance and outlined against the sky, was an apparently never-ending line of French artillery, appearing over the edge of the hill, passing across a long straight stretch of road where according to French custom, trees were set at regular intervals. I was fascinated with the picture which they presented, but Miss Tyler said that she had seen so much of the horrible side of war that she could see nothing picturesque about it. It seems as though it must be over by spring. “

Armistice

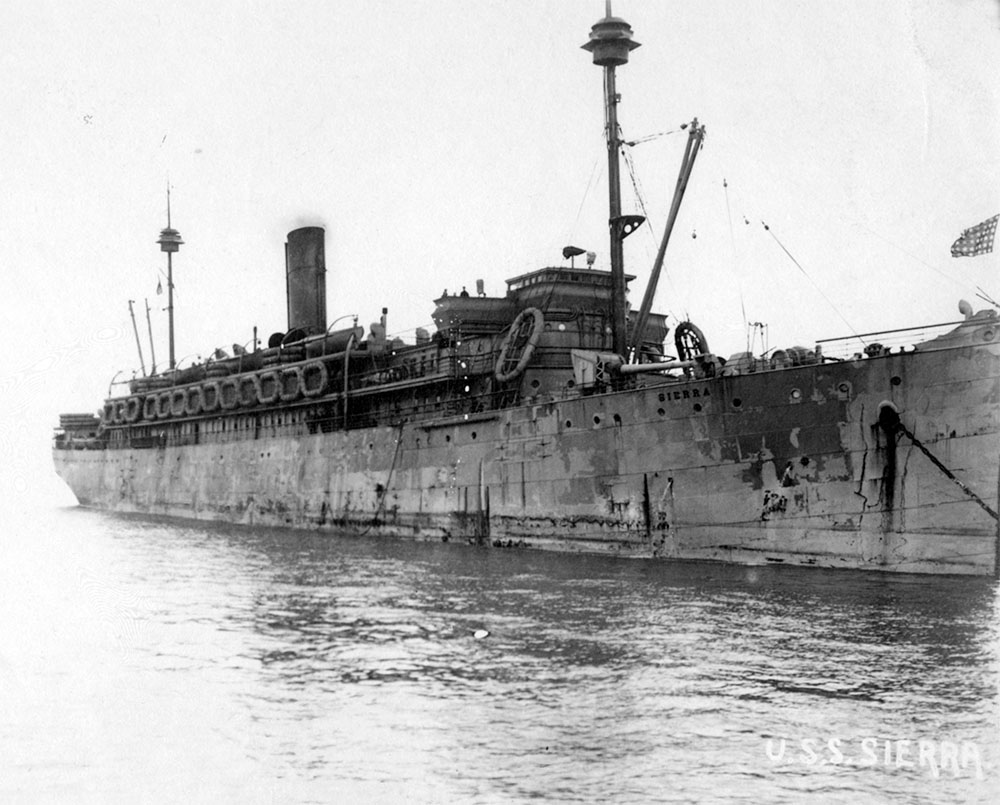

Three weeks later, November 11, 1918, an armistice was signed. Demobilization took time and Marguerite returned to the states with the 82nd Division. They departed Bordeaux, France aboard the transport ship Sierra on May 9th and arrived in New York on May 21, 1919.

Back in the states, Marguerite enrolled in a hospital training course at the Presbyterian Hospital in connection with Columbia University in New York. She married Myron Wilcox, a First Lieutenant in the Army during WWI, in New York in May 1923.

The couple moved to Cedar Falls, Iowa, where Marguerite gave birth to a son on January 31, 1925. Just two weeks later on February 14, she died of puerperal fever (childbed fever) in Iowa City, at the age of 35.

Marguerite is buried near her grandparents in Glenwood Cemetery in Mankato. An excerpt from her obituary in the Mankato Free Press reads: “There are lives made stronger by adversity. For Marguerite Marsh, one after another the home ties of her girlhood were broken by death. Through it all, she preserved her brave faith, the sweet poise of character that carried her through to a fine womanhood in a happy home of her own.”

Marguerite Marsh and Maud Hart Lovelace

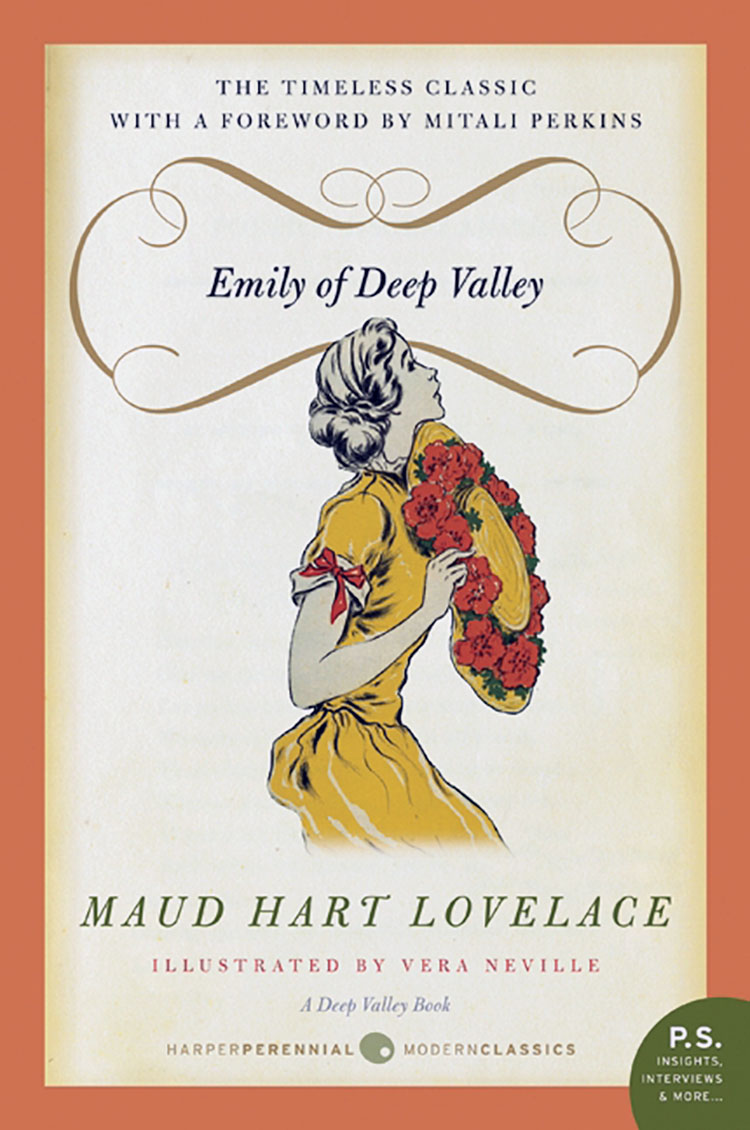

Marguerite Marsh was a high school friend of author Maud Hart Lovelace. Lovelace based the book, Emily of Deep Valley on the pre-war life of her friend Marguerite (Emily). “In many ways, Emily of Deep Valley told a true story,” Lovelace wrote in 1973.

This book is a great read over the Memorial Day holiday. Not only does it give us insight into Marguerite’s life, but Lovelace gives accurate accounts of a “Decoration Day” celebration in Mankato (fictional Deep Valley) and the tradition of decorating the graves of soldiers and family.

Marguerite suffered many tragedies in her short life, and she always coped admirably. The similarities between Marguerite and the character of Emily make it apparent that Marguerite’s life left a deep impression on Maud. This book is a great story (fiction based on fact) of coming of age and learning to deal with what life gives you by turning disappointments into new and wonderful opportunities.