Although it’s been gone for over 30 years, the grandeur of the Schmidt House sparks fond memories for those who remember it and those who have only seen it in pictures. What is the story of the people who built and lived in this house?

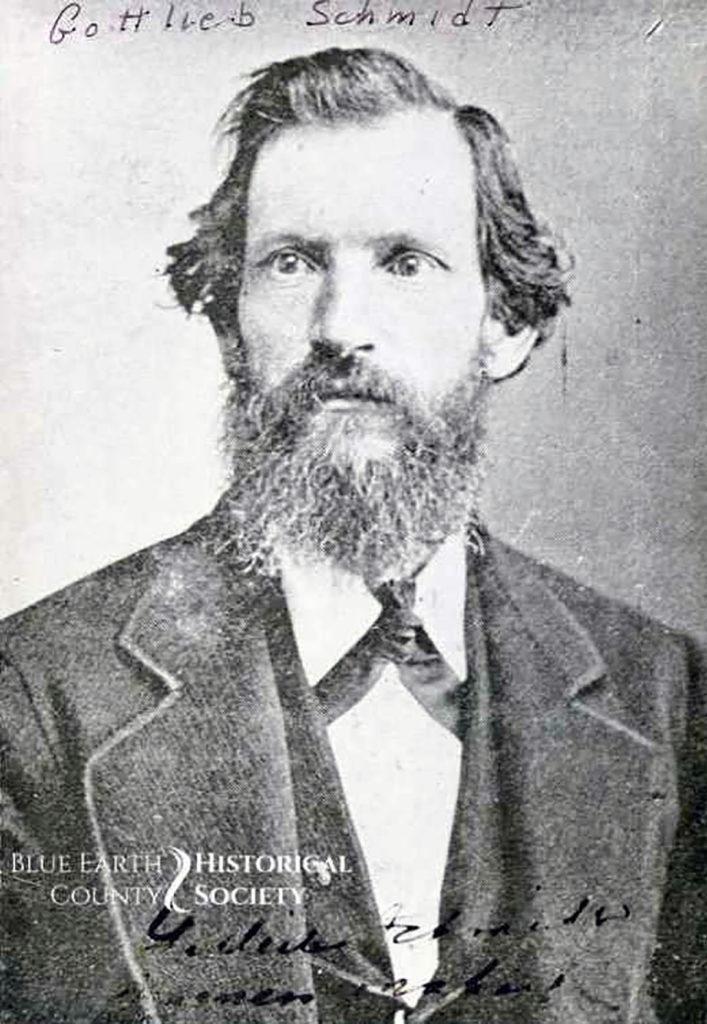

The story begins in Saxony, Germany where Gottlieb Schmidt was born in 1826 and as a young man learned the trade of harness maker. He emigrated to Minnesota with his two brothers, arriving in Mankato by steamboat in 1854. At the time there were only a few log and frame buildings along Front Street and very few horses in the county.

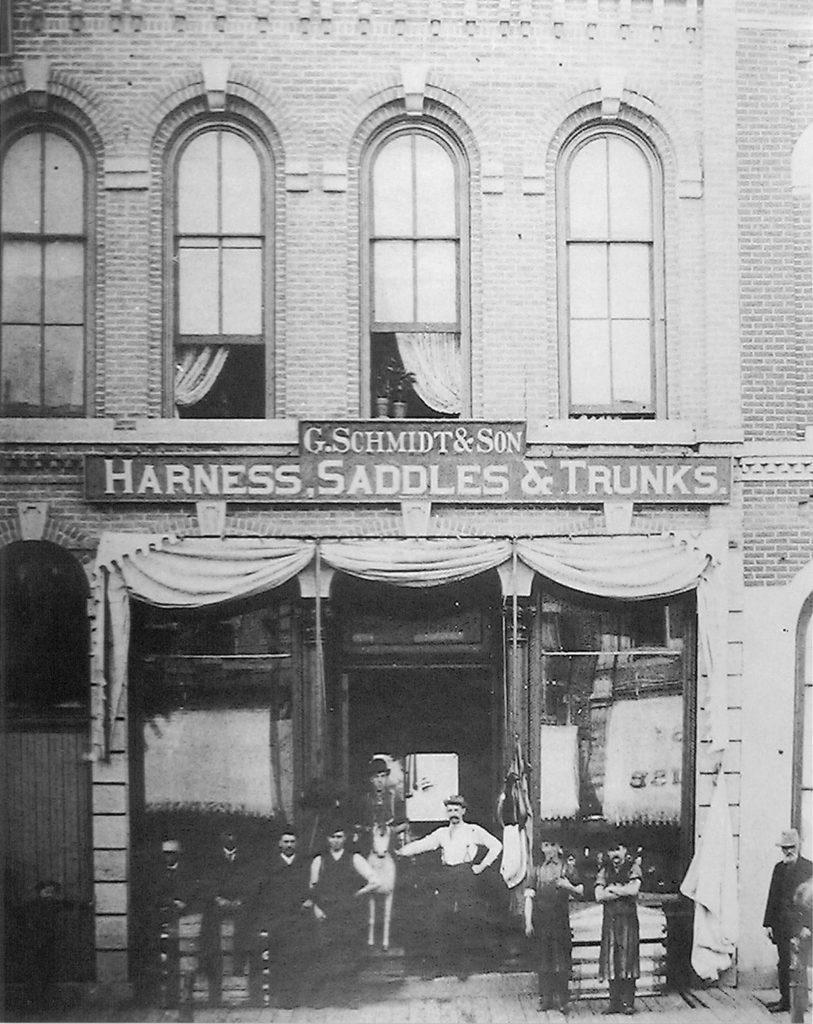

By 1859, he and Henry Bergholtz, also a harness maker, had opened a harness making shop on Hickory Street. It was Mankato’s first harness business and would eventually become one of the largest and best-equipped harness manufacturing companies in southern Minnesota.

The harness shop moved to 226 South Front Street in 1861. Business was greatly increased by government contracts during the Dakota Conflict the following year. With the rapid settlement of the area after the war, business continued to thrive serving the needs of farmers and horsemen by making and selling horse harnesses, saddles, and trunks.

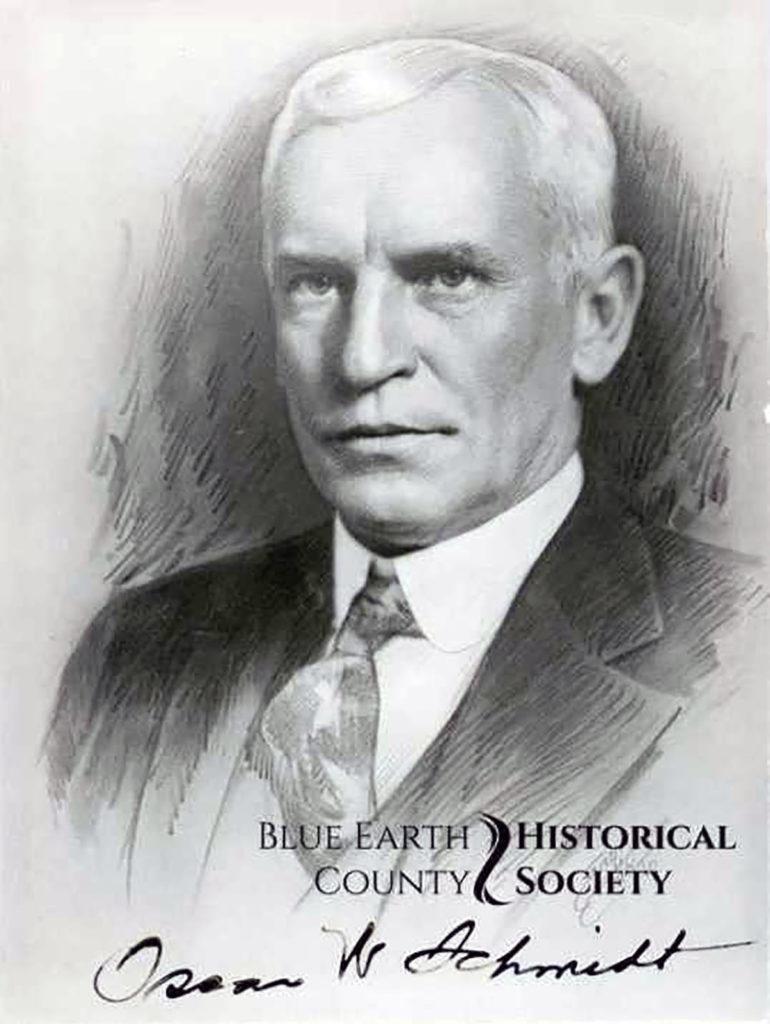

Bergholtz retired from the business in 1868, leaving Gottlieb as the sole proprietor. When Gottlieb’s son, Oscar W. became his father’s partner in the firm in 1887, the name was changed to Gottlieb Schmidt & Son. Their partnership continued until 1896 when Gottlieb passed away. The store name was changed to the O.W. Schmidt Saddlery Company (later known as Schmidt’s Leather Goods).

Second Generation

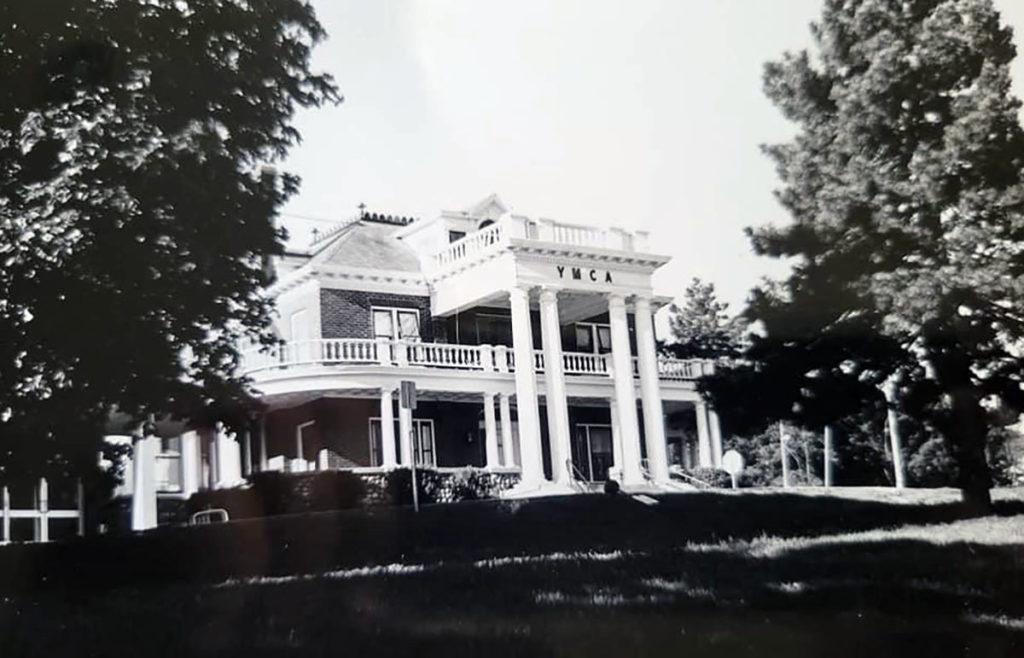

Oscar and his wife Katherine began construction of the iconic Schmidt House in 1923. The house was built on a hill overlooking South Front Street (now South Riverfront Drive) on the site of the old John Marsh home (see Marguerite Marsh and the YMCA in the Great War).

The two and a half story red brick Neo-Classic style house was designed by local architect Henry C. Gerlach Jr. and construction took nearly two years to complete. The dominant feature of the house was the two-story front entrance portico, supported by two columns at each front corner and topped by a balustrade.

Henry Gerlach Jr. and his father were prominent Mankato architects and designed many area buildings, some of which are now listed on the National Historic Register. In fact, the Oscar Schmidt House was also listed on the register in 1980.

Oscar and Katherine had one son, Harold, who became his father’s business partner in 1926. The horse was gradually being replaced by the automobile which led to the closure of the harness department. Merchandise shifted to luggage, purses, gloves and belts, cameras and photography supplies, and other gift items.

In 1931, Harold married Magdeline Henke and the couple lived in the spacious home with Harold’s parents. Later they had two sons, Jerry and Roger, who grew up in the Schmidt House.

The Schmidt “Mansion” remained in the family until 1958, when the YMCA acquired it for office space. In 1988 a $1.2 million expansion project was planned by the YMCA and despite petitions from the Save the Schmidt House Committee, the city council approved demolition. The house was only 65 years old when it was town down.

What was the Schmidt House like?

The main floor had a living room with a fireplace that was often used. In the formal dining room were large built-in storage cabinets for china and dishes. Under the dining room table, where the lady of the house sat, there was a button to push when one wanted to summon help from the kitchen. There was a library with another fireplace, a kitchen with built-in cabinets and appliances, a bathroom, a large walk-in closet for clothes storage and a sunroom room with lots of plants. There were two large vestibule rooms by the front and side entrances. A tool room opened into a double garage that had underground tanks for gas storage and a gas pump.

Two stairways led to the second floor. The front stairway led to a wide hallway with four bedrooms. At the front were double glass doors that opened into a sitting room with a desk and couch. Two more glass doors opened outdoors onto a balcony that curved around the front and one side of the house. There was a full bathroom on this floor and a clothes chute to send dirty laundry to the basement area.

A back stairway led to two bedrooms for the maids. There was also an incinerator here for burning paper. If the incinerator was lit from the bottom, it would smoke the whole house up! In later years one of the back bedrooms was used as a model train room.

The third floor was a large open attic. One corner was full of toys where the children sometimes played. There were also doors to an outside balcony on this floor, where the children played with friends in their teen years.

Every window in the house had a lace curtain and each spring they were taken down and laundered, which was a big job. After they were washed, the curtains were stretched on rods at the top and bottom while they were still wet to prevent them from shrinking and losing their shape while drying.

The basement had a large L-shaped recreation room that contained a ping-pong table and a fireplace. There was a large laundry room for washing, drying, and ironing clothes, a furnace room, a storage room that contained lots of screens and storm windows, a vegetable room that contained canned fruits, vegetables and dandelion wine, a huge cistern and another bathroom. This bathroom was converted to a darkroom for photography in later years.

The Women of the House

While Oscar managed the business, his wife Katherine managed the home. Katherine shared many interesting stories with her grandsons, Jerome and Roger, of her early years living in the area. One of these stories was that the Native Americans lived near the area where she and Oscar lived. One winter was particularly bad with drought and cold. The Indian’s came to ask for food, but she said, “They never begged!” She would give them what she could such as flour, meat, and staples to help their families. They always gave her something in return—their handmade pottery or whatever they could afford in the hard times.

Katherine was a gracious and strong woman, thoughtful and loving. She baby-sat and played games with her grandsons. The boys remembered walking through the large house holding grandma’s hand to find the cause of a “strange” noise (she always had to know what it was!). Kate was an artist, and a large oil painting was on display in their library that she had painted in oils.

Katherine’s greatest passion was her love of growing things. Her specialty in the yard was lilies. Inside the house there were lots of plants and she grew African violets in abundance in the sunroom. Katherine Schmidt worked to the last day she lived in the home that she loved. In 1950 at the age of 76 she collapsed and died suddenly while setting the table for lunch.

Magdeline Henke Schmidt grew up being the only daughter with four brothers. She was athletic and enjoyed outdoor activities with her brothers. She was a good tennis player and ice skater. She skated for Mr. Johnson of the Shipstads & Johnson Ice Follies when they had trials at the North Mankato ice rink.

Before her marriage to Oscar, Magdeline worked as a secretary to the president of Mankato Teachers College (now Minnesota State University of Mankato). She was active in dance club, book club, cub scouts and many other local and civic events. As a member of the Eastern Star, she was awarded “Worthy Matron of the Eastern Star.”

Together Magdeline and Katherine created happy and special occasions for their family, with birthdays and Christmas being the biggest celebrations. Both women were excellent cooks. Magdeline created a family handwritten recipe book of their favorite recipes. They both loved fine china, glassware, and silver service. Fine linens were often hand embroidered or monogrammed by Katherine and Magdeline. Katherine created beautiful crocheted bedspreads. Magdeline did crewel embroidery and Scandinavian design sweaters. Their greatest team efforts were the many beautiful quilts they created.