Most people wouldn’t consider the months of January and February a season of harvest in Southern Minnesota. But in our not so distant past, this was harvest time for—ICE. Rivers, lakes and ponds are generally frozen and ice was harvested like a winter crop to keep food cold all summer long.

Before modern refrigeration, ice harvesting from frozen lakes and rivers was an important industry that required hard work and careful planning. Ice was crucial for railroads to cool boxcars for the shipment of fruits, vegetables and meat. Ice was needed for butcher shops, creameries, stores and breweries.

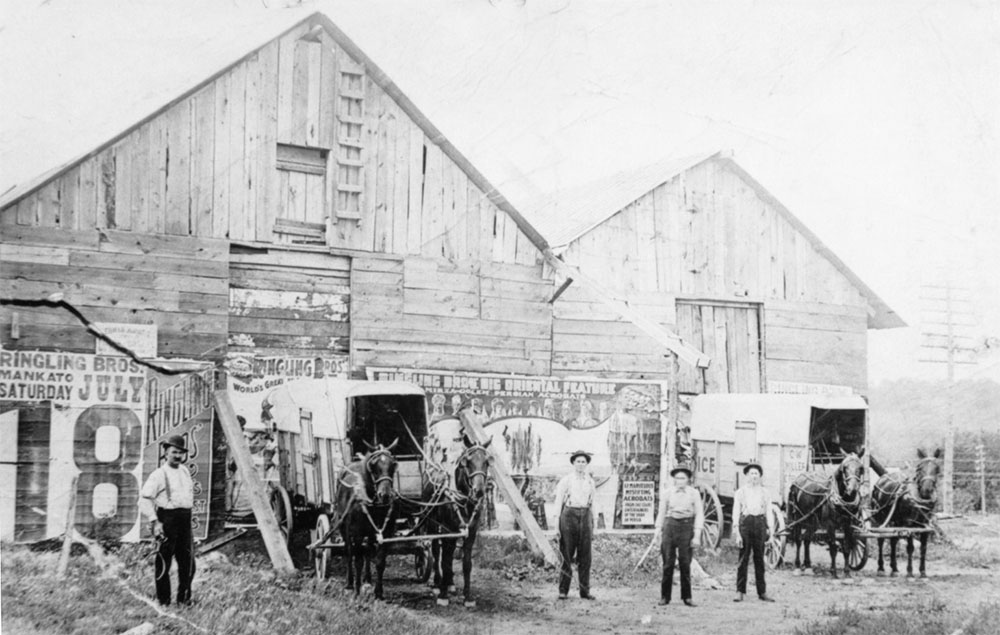

Once one of Mankato’s oldest and vital industries, the ice industry flourished as five companies competed for a share of the business in the early 1900s.

In 1900, Charles W. Miller became a partner in the ice business owned by Adolph Lilly. The business became the Miller Ice Company when Charles assumed sole ownership. Miller Ice Company would have several owners throughout the years including Herman Held, Harry Miller, Clayton Miller, Al Gilquist and Gordon Ballman.

You may not believe it, but the ice in the Blue Earth river is as clear as any in the state. One year I procured a cake twenty inches thick and could read legal notices through it from a newspaper placed on the other side.

Miller’s office and main ice storage houses were located between the 500 blocks of Owatonna Street and Hubbell Avenue, the present location of the exits off Highways 169 and 60 next to the YMCA. The company also had ice storage houses in LeHillier and on Lake Street near Spring Lake Park in North Mankato.

The Miller Ice Company, later known as the Mankato Ice Company, was Mankato’s longest running ice business.

The Ice Harvest

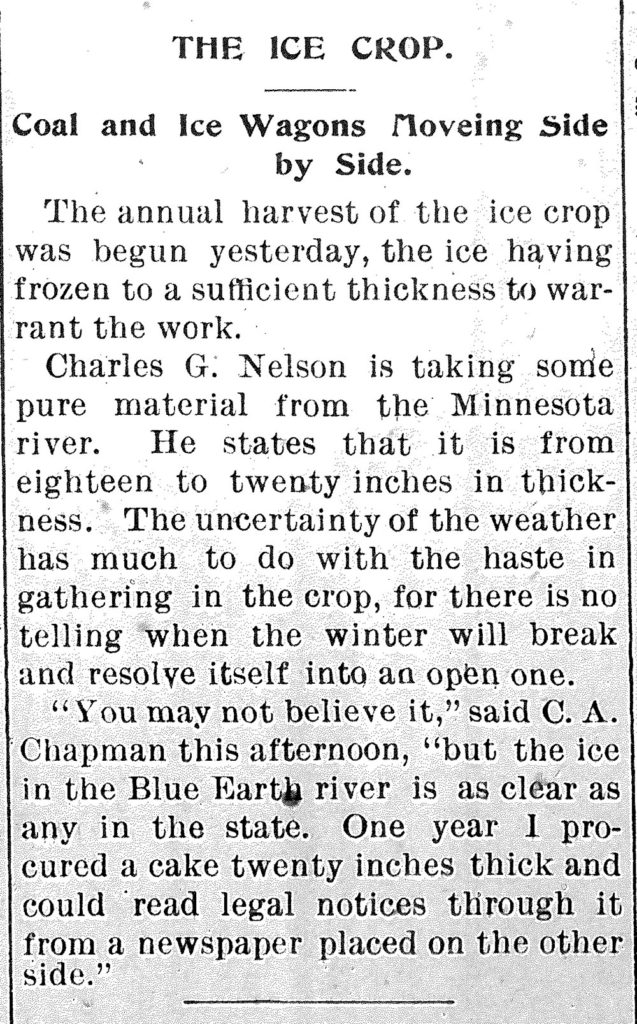

Mankato newspapers regularly reported on the ice harvest. In 1895, C.A. Chapman told the Free Press; “You may not believe it, but the ice in the Blue Earth river is as clear as any in the state. One year I procured a cake twenty inches thick and could read legal notices through it from a newspaper placed on the other side.”

The natural ice cut from the rivers and lakes was tested regularly by the State Health Department and found to be pure. Nature purifies the water as it freezes, forcing dirt and bacteria into the water below.

Most of the ice harvesting for Mankato was done on the Minnesota and Blue Earth rivers and Spring Lake in North Mankato. In 1898 the Free Press reported, “the ice was taken from the mouth of the Blue Earth river, where the Minnesota spreads out and there is very little current to cut the ice away from underneath”.

The harvest provided employment for men and teams once the ice had frozen to a sufficient thickness. The ice had to support the weight of the men, horses and equipment and to make ice blocks thick enough for efficient use. At the height of the season between 65 and 75 men, many of them farmers, would work removing the ice from the river.

Cutting ice was cold, hard work requiring long two-handed saws, giant tongs, chains, ropes and horse-drawn ice plows to score the ice and wagons to haul it to storage. “We would wait until the river ice was about 14 inches thick before we started to assemble our equipment on the shores,” Harry Miller told The Free Press in 1952. First the men prepared the ice field by clearing off the snow. “When the ice was “ripe” a horse drawn cutter would plow back and forth over the river surface, cutting the cakes into pieces of about 18 x 24 inches. Teams with sleighs hauled the chunks to shore with chains and loaded them into horse-drawn wagons or sleighs to be taken to the storage barns.”

Though the men were working with sharp saws and piercing ice picks, the greatest danger for workers was falling into open water. Tools could also be lost by falling into the water. “I imagine I’ve fallen into the water about 10 times, but none of us have ever drowned doing this. There are always co-workers around to get you out. The job is most perilous just before daybreak when you may not be able to see certain slippery edges on the ice,” Clayton Miller said. When temperatures rose to 35 degrees, the work could not proceed because the ice became too slushy to pack.

In 1902, high costs led to labor disputes. Teamsters hauling for Hammann & Polchow Ice Company demanded higher wages due to the high cost of feed for their horses and the horses had to be frequently shod because hauling up hill was so hard on them. The haulers were being paid $2.50 per day and were striking for $3 per day. The men typically worked from 6:30 am through 5 pm. There was also a rivalry between teamsters and farmers. Farmers were able to feed and keep their horses more cheaply than they could be fed and housed in the city. This led to the city requiring farmers to obtain a license to work in town.

Some years the temperatures did not allow for a long harvest season and would therefore result in a reduced harvest. This would create a shortage come summer, as was the case in August 1919. Ice had to be obtained from Stillwater or Minneapolis and shipped by rail. However shipments were irregular and expensive due to shipping and shrinkage. Residents were asked to reduce all unnecessary use of ice to conserve.

I imagine I’ve fallen into the water about 10 times, but none of us have ever drowned doing this. There are always co-workers around to get you out.

Frank Reedstrom, a Rapidan farmer, started his own ice business when he needed to cool the milk from his family dairy farm. In the 1920s and 1930s, he cut ice from Rapidan Lake. They used to harvest 4,000-5,000 blocks of ice per year in addition to the 3,000 blocks they put up for the Rapidan creamery, charging between five and six cents per 250-pound cake of ice.

Farmers often got together and cut their own ice and kept it in their own ice houses. For many farmers, ice harvesting continued until electricity reached the rural areas of the county, which came much later than for Mankato and other smaller communities.

Reedstrom remembered using a Model T Ford motor and a 36” lumber saw made by Emil Bartsch of Rapidan. This saw used every bit of energy the motor had to cut into the ice and could cut up to 13 ½ inch furrows. Each row of blocks was cut apart with a breaking chisel, a large piece of wedged metal. The ice was cut into 20 x 24 inch blocks that were then guided to a conveyor, run by a motor or power take off from a tractor, which moved the block into a vehicle. “Cutting ice could be tricky. If the ice furrows were cut too deep, the ice would heave, and because of the pressure under the ice, it would break through and freeze the furrow”. Weather could also be a problem. “We cut ice when it was minus 35 degrees. Chains would break, steel will freeze too and then it gets like glass,” said Reedstrom.

Icehouses

When the ice-filled wagons or sleighs arrived at the icehouse, they backed up to the runways, and the ice cakes were slid into the building where a crew of six men in each barn arranged the ice. About eight inches around the outside walls of the barns were filled with sawdust, and the ice was covered with a 10-12 inch thick layer of sawdust. The crew of men constantly raked and filled the holes with the sawdust. Sawdust acts as an insulator, slowing ice’s melting. With ventilation and good drainage, an icehouse, could keep ice cold until the following winter. Once a mass of ice is in one place, it’s hard to melt it just because of the sheer volume.

Later when the “sleeping” ice was taken out for delivery, the men uncovered the cakes and slid the blocks down the runways to the waiting wagons. The ice would be washed near the barns, taken to the point of delivery, chiseled into shape with a hatchet and washed again at the destination.

The storage of ice was not the only work involved at the icehouse. An average of 25 tons of hay, six loads of straw, 1000 bushels of oats and between 40 and 100 tons of sawdust from the Mankato area sawmills was used in its operation each year. These were all the essentials for the effective storage of 10 to 12 tons of ice a year and were kept in the Miller Ice Company’s six barns.

During the period up to 1920, the physical plant of storing and delivering ice for home refrigeration, to fruit markets and stores, grew in size and quantity. By the year 1917, Miller had eight teams and wagons in operation in Mankato.

The disappearance of the horse from the streets of Mankato led to the purchase of the first “solid wheeled, chain drive Reo truck” to be used to haul ice.

In 1948, Gordon Ballman purchased the Miller Ice Company and renamed his business the Mankato Ice Company. Ice harvesting in the Mankato area came to an end when Ballman installed artificial ice-making equipment at the Owatonna Street location in 1952. The last ice-storage houses in Mankato were removed and a modern plant was built.

The new plant produced 24 tons of ice in 400-pound cakes every 24 hours. At the time Mankato could boast the only artificial ice-making plant in the state outside of St. Paul. Long time customers, the railroads, who used ice to refrigerate their passenger cars as well as the box cars carrying produce, were joined by semi-trucks hauling produce from the South made Mankato Ice Company a regular stop.

When Highway 169 and 60 came through West Mankato in 1959-1960, the ice plant and many other business and residences were removed to build the approaches to the new bridge over the Minnesota River.

Ice Delivery

In the early years, residents were familiar with the sight of the ice wagon pulled by a team of horses through Mankato streets, stopping at nearly every house to deliver a cake of ice.

Depending on both the season and day of the week, many icemen worked seven days a week and through holidays. The ice delivery crew rose at 4 am to feed the horses, clean harnesses and load ice. Deliveries began at 5:30 a.m. and the men generally returned about 7:30 p.m. to clean and feed the horses.

During wet and rainy weather, wagons had to trudge through muddy streets. “Mud was often a foot deep on the city streets in those days and men wore rubber boots when making their deliveries,” recalled Harry Miller.

Customers posted their “Ice Today” sign in their window and eagerly awaited the crystal-clear cakes with which to stock their “ice boxes.” Some homes had small doors that opened to the icebox from the back porch. The iceman brought the block of ice and inserted it into the icebox through this door. The ice cakes were hauled into homes on the iceman’s leather covered shoulder using smaller ice tongs.

Iceboxes were typically made of wood, lined with tin or zinc and insulated with sawdust. The ice block would last one or two days during the hot summer months. A small drain built into the icebox would direct the melted ice water into a pan underneath the icebox. This pan had to be emptied frequently to avoid getting water all over the kitchen floor.

There is a nostalgia about the passing of an era when the arrival of the iceman was eagerly awaited on hot summer days.