In April 1965 26-year-old Bob Kreuzer joined Frank Morse, a Kato engineering co-worker, along with employees from the City of North Mankato, to watch over the operation of city pumps that sent sewage from North Mankato to the City of Mankato Water Treatment Plant.

A central, underground collection point called a lift station, located near Highway 169, sent the waste by way of a pipe on the floor of the Minnesota River. The station housed four pumps in two separate rooms. Two of them were powered by electricity and two others were powered by gas engines.

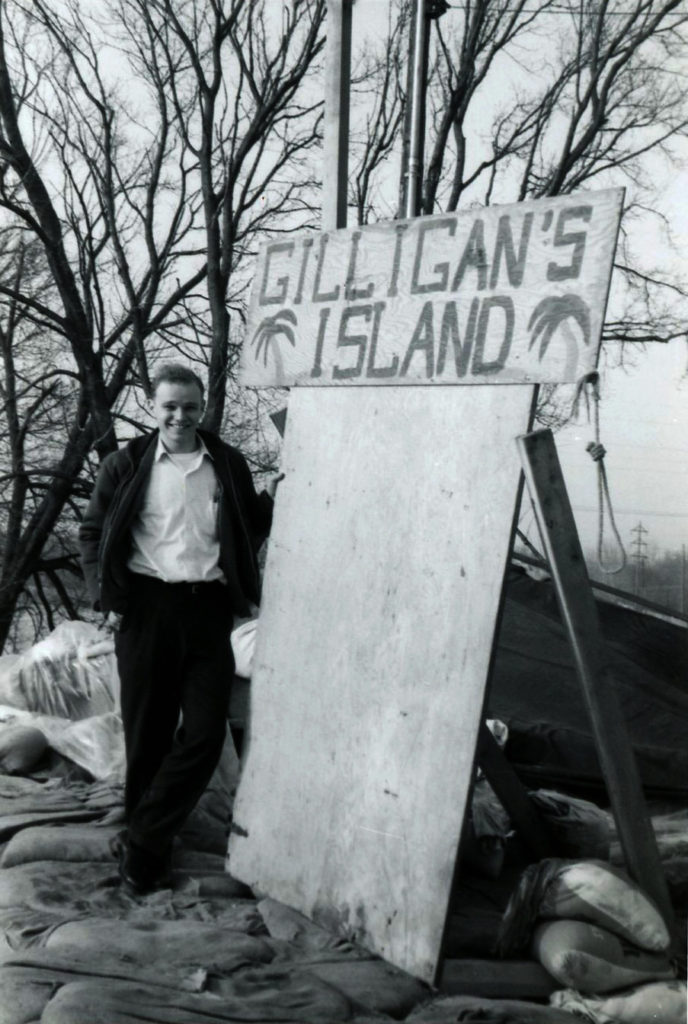

Pictures and stories of ‘Gilligan’s Island’ recall a time when a small group of workers and volunteers gave the city a moment of pride and confidence that it could overcome any challenge

As it became clear in 1965 that a flood was inevitable, officials needed to find and fix any problems with the pumps in the shortest amount of time possible. The backup of sewage from North Mankato into flood waters would spell an entirely different kind of disaster.

A Late Spring

Those who remember the 1965 flood of the Blue Earth, Minnesota, and other rivers in southern Minnesota tell of more-or-less typical weather during the winter of 1964 and 1965. That is, until March when hefty amounts of snow, blustery blizzard conditions, and frequent below-zero temperatures delayed the arrival of spring. When spring eventually did arrive, it quickly created conditions ripe for flooding.

It was believed the system of dikes along the Minnesota River in Mankato and North Mankato could handle a river height of up to 25 feet. On April 7, 1965, a U.S. Weather Bureau climatologist predicted the river would crest at slightly more than 26 feet. By the time the river was done cresting in mid-April it had reached 29 feet.

As the crest neared, the two cities, separated only by the river — the distance of only a couple of blocks — and joined by the Main Street bridge, found themselves facing the challenges of a history-making flood. Filling burlap bags with sand to build dikes, pumping water, and using dozens of culverts in the area to direct the water became the front-line strategy.

The Lift Station

In 2020, the lift station sits safe and dry in the same location as 54 years ago on the land between the Minnesota River and Highway 169. But in 1965, river water gradually flowed over the banks threatening the operation of the pumps.

In response to the threat of imminent flooding, workers began placing sandbags around the station. As the flood waters rose, covering what was once dry, flat land, more and more sandbags were added, finally reaching a height of six to seven feet.

Now isolated by water, a duck-hunting boat ferried workers to and from the lift station from the edge of Highway 169 and the workers and volunteers propelled the boat with a long pike pole speared through the water to the ground below.

The American Red Cross delivered sandwiches and similar fare for those engaged in the battle to keep the station working. The duck-hunting boat carried the food to the lift station from where the Red Cross truck was parked along Highway 169.

The duck-hunting boat came in handy for more than just the commute back and forth to the lift station. It was used to retrieve things floating in the flood’s current, including a full extension ladder!

The sandbag walls of the lift station were successful at holding back the floodwater. With water on all sides, the station became a small man-made island not far from the intersection of Highway 169 and North Mankato’s Webster Avenue.

Gilligan’s Island

Eight months after CBS introduced a sitcom about seven stranded castaways, one night during the second week of the flood, a hand-made sign went up on the lift station island, declaring the name to be Gilligan’s Island forever connecting the show with an episode of Mankato’s history.

The name didn’t go unchallenged as two-way radio communications were heard one weekend offering the alternative moniker, Alcatraz.

Sibley Park and West Mankato

Local flood control officials expressed their concerns about the before-and-after challenges presented by the flood threat, which came upon the sister cities with little time in which to prepare.

Going into emergency mode, they called out for help from a wide selection of people from both communities, some with special tools and skills and others with nothing more than a desire to serve.

On Thursday, April 8, 1965 the call for volunteers became significantly more urgent as a primary dike alongside the river at Sibley Park broke in the mid-afternoon, sending the floodwaters into the park and the low-level neighborhoods of West Mankato.

Blue Earth County, with Mankato as the county seat, declared these sections of Mankato a disaster area in the early morning hours before the dike broke, when residents and businesses were ordered to evacuate. Minnesota National Guardsmen quickly moved in to provide sentry duty right after the evacuation.

Lower North Mankato

The people of North Mankato did not wait to receive an official declaration or order of evacuation. Hearing about the chance of imminent flooding, they took it upon themselves to protect their possessions and safeguard their families.

During North Mankato’s voluntary evacuation, Tom Bohrer, the former owner of the Circle Inn Bar, recalls that as a ten-year-old, he pitched in and helped his family move all their furnishings out of his family’s lower North Mankato home. After securing their own home, Bohrer and family moved on to help other neighborhood families do the same.

Bob Kreuzer got word that he was tasked with aiding the company’s North Mankato employees, like Kurt Steinburg, to remove many of their larger household items to higher ground. He was assigned a Kato Engineering truck to help with the moves. The young employee’s call to action came directly from the company’s president, Cecil Jones.

Meanwhile, Back at the Lift Station

After assisting with evacuation, Kreuzer and his co-worker Morse drove through the near-empty city, which was as quiet and still as a ghost town.

They steered into the parking lot of the North Mankato City Hall. Once inside the city hall building, city leaders recruited Kreuzer and Morse as volunteer monitors watching over the pumps at the lift station when the regular city workers were off duty or attending to other flood-related assignments.

Working with the lift station’s mechanical and electrical equipment fit Kreuzer perfectly. He expressed his eagerness to get into the mix and be of service. And like the others, he accepted painful typhoid shots as a precaution against an infection from the potentially polluted and infected floodwaters.

Though there were plenty of people from the community and surrounding areas who volunteered to help fight the flood, few wanted to volunteer to be in a location twenty feet below the ground with floodwaters rising above. Kreuzer and Morse frequently received requests to come back to the lift station to fill extra shifts.

Bob Kreuzer

Kreuzer had arrived in Mankato in 1958 after graduating with a two-year electrical general degree from Dunwoody Institute in Minneapolis.

That year there was a sharp global economic downturn. It was the first recession after the post-World-War-II-boom. Because of the economic conditions, it appeared impossible for Kreuzer to land a prestigious position with an electronics company in the Twin Cities. Job openings for which he was qualified were few and far between. Instead, he accepted a job at Kato Engineering in Mankato as an engineering assistant, a job offered by Cecil Jones, who also was a Dunwoody Institute graduate.

Between his hiring at Kato Engineering and the 1965 Flood, Kreuzer took on every entry-level “shop” assignment given to him by his employer, performing basic tasks in most of the company’s engineering, manufacturing, and product testing departments. He learned how the company’s skilled employees built the products, and how the finished products worked. He also knew how to get the most from Kato Engineering generators and voltage regulators in this unique application.

By the time he first descended into the lift station pump rooms in 1965 with floodwaters rising above him where once there was dry land, his knowledge of electrical and mechanical principles was proven and ready. When he arrived on the scene there wasn’t even time for on-the-job training. But his education and skill enabled him to continue volunteering his time until the threat of flooding was past.

In December, a 24-year-old woman named Louise asked Kreuzer to dance the polka with her at Harry’s Hofbrau House in the Burton Hotel. Kreuzer didn’t know how to dance but she patiently taught him….

Kreuzer also belonged to the Mankato Area Radio Club, a collection of short-wave ham radio operators in southern Minnesota. Typically, these operators used their radio time talking to people from all over the United States and the world. During the 1965 flood, club members assisted Civil Defense and local law enforcement in communicating about the conditions of the sandbag dikes around Mankato and North Mankato.

With the large numbers of people pouring into Mankato and North Mankato to help, wired telephone and telegraph services were stretched to their limits so the assist of short-wave operators was especially important.

Pump Failure!

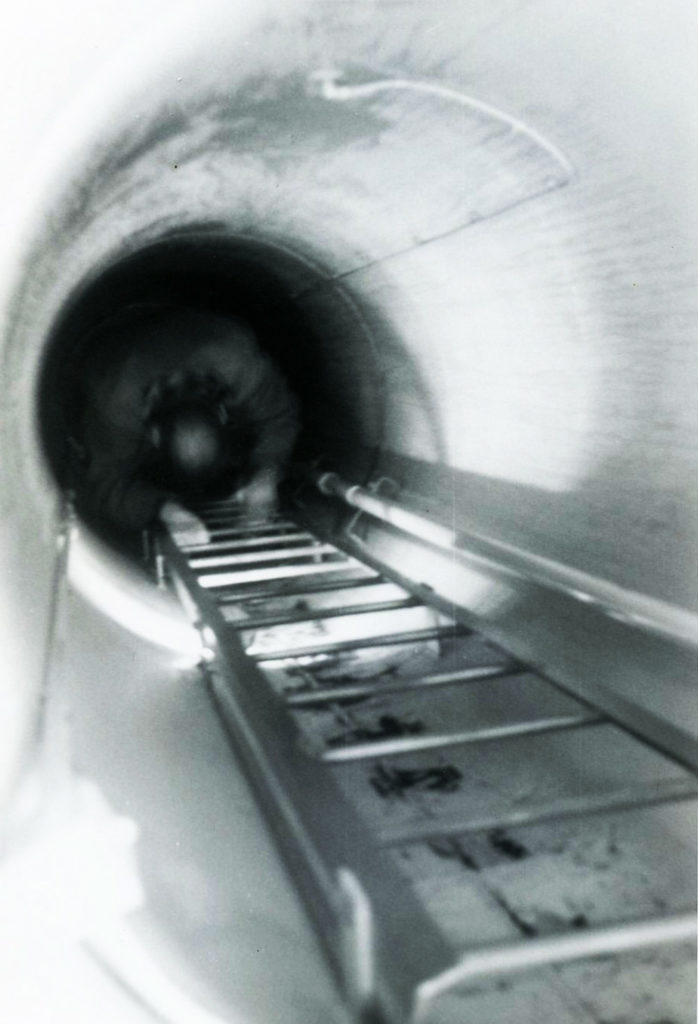

Kreuzer noted that the room for the electrical pumps shared little in common with the room for the gas-powered pumps. A steel shaft and ladder led to the steel-encased room that housed the electrical pumps. In stark contrast, wooden steps led to the room for the gas engine-powered pumps with walls of cement block and heavy timber for reinforcement.

Every contingency the engineers could conceive of for problems with the pumps and their environments was mapped out and there was a sense that “Gilligan’s Island” stood prepared to deliver uninterrupted service.

But just as the flood was cresting, water started to seep, then stream through the mortar joints of the block wall of the gas engine-powered pump room. The wall caved in, the room was flooded, and the gas-powered pumps were lost. Fortunately, there were no employees or volunteers in the room when the wall caved in.

Also, fortunately, the lift station was able to continue functioning adequately with just the two remaining electrical pumps until the river began to recede.

Recovery

Gawking at the Main Street Bridge lost its luster as crowds watching the river water level there began to thin out.

On April 14 and 15, North Mankato citizens who abandoned their properties in the city’s lower sections began returning to their homes and businesses.

North Mankato’s “Gilligan’s Island” quietly faded into local lore as area residents focused on clean-up and returning life in both cities to normal.

A Banner Year!

Flush with tales from the flood and his continued growth on the job as an engineering assistant, 1965 proved an extraordinary year for young Bob Kreuzer. In December, a 24-year-old woman named Louise asked Kreuzer to dance the polka with her at Harry’s Hofbrau House in the Burton Hotel. Kreuzer didn’t know how to dance but she patiently taught him. Two years later, Louise and Bob married. They remained married for over 40 years until Louise passed away in 2010.

Kreuzer retired from Kato Engineering after 39 years of employment and has been a resident of both Mankato and North Mankato ever since he left the Dunwoody Institute to this day.

From the vantage point of the present, pictures and stories of “Gilligan’s Island” recall a time when a small group of workers and volunteers gave the city a moment of pride and confidence that it could overcome any challenge.